Today’s chips are hard to make from potatoes or EU policies

One area where the EU has become increasingly interventionist in its industrial policies is in the semiconductor industry. In her 2021 ‘State of the Union’ speech, the European Commission President Ursula van der Leyen commented that there is “No digital without semiconductors”.

In many ways the statement is tautological, bearing in mind that ‘semiconductor’ is a general term used to describe electronic components such as microprocessors, memories, image sensors and disk drives, among other things.

Macroeconomic instability and an increasingly volatile supply chains have, along with a wider systemic shortage of semiconductors in recent years, induced calls for policy interventions in order to increase supply and make it more reliable. The EU Chip Act can be regarded as the EU’s combined attempt to counter these challenges. Its overarching goal is to ensure that at least 20% of the value of all semiconductor production should take place in the European Union by 2030.

This goal should be achieved through what the EU refers to as ‘policy-driven’ investments, amounting to €43 billion over the coming eight years.

The Chip Act is made up of three pillars. The first is aimed at turning the EU into a leading player in the development and design of semiconductors. These efforts include the creation of competence centres, funding of research and attempts to increase supply of venture capital to the sector. A tranche of the resources will be relocated from the EU’s Horizon research programme.

The second covers attempts to stabilise the supply of semiconductors in the EU. Support for establishing factories is an important part of these efforts. As the production of semiconductors is highly capital intense, the EU argues that additional support and funding efforts are required from its budget.

The third contains efforts to monitor the industry and identify and highlight potential shortages before they occur. The European Semiconductor Board will monitor the industry and immediately inform the European Commission if it believes a shortage is likely to occur.

EU will not be leading in semiconductors

The first pillar is unlikely to deliver neither significant positive nor negative effects. There are no signs that the EU is anywhere near the ‘leaders’ in the field of semiconductors, and it would be naïve to believe that it will become so from these efforts initiated by the European Union.

One potential downside to this initiative relates to the fact that these funds will be taken from EU’s Horizon budget. Horizon research money has always been organised through a competitive process, over which individual Member States have little influence. In the case of the Chip Act, Member States will exert greater influence, leading to potentially suboptimal outcomes and vote trading.

Chip Act likely to benefit interest groups

The second Pillar, which is relates more to production capacity, poses potentially greater problems. Few sectors have been as unpredictable, turbulent and dynamic as the semiconductor industry. Large-scale policy interventions in such an industry are inherently dangerous, and may lead to heavily dysfunctional outcomes. Semiconductor manufacturing is a highly sophisticated process, there are currently very few ‘fabs’ in the world and very few firms or regions possess the capabilities required to build such facilities.

Since the Chip Act was put in place, Intel has announced its intention to invest €83 billion in Europe in the coming years. Intel has also ambitions to build a plant in Germany at a cost of €19 billion. At the moment, it is currently not clear what proportion of funding for these will come from the EU.

As countries and trading blocs around the world are increasingly desperate to secure a domestic supply of semiconductor manufacturing, chip companies have found themselves in a highly favourable position. The US, China and EU are currently seeking to outbid each other to attract investments. As the industry is heavily capital intense, the dominant players such as Intel, TSMC and Samsung are well capitalised and would arguably be able to finance their own investments. In a political negotiation between a set of global firms and a European Union handing out taxpayer money from the Member States’ citizens, there is an inherent risk that these firms will get the better of the deal. Intel has lost a great deal of its competitiveness in recent years and the EU would probably have been better-off working with TSMC; however, in processes such as this, politics and subsidies matter more than competitiveness and capabilities.

The Semiconductor industry is highly dynamic

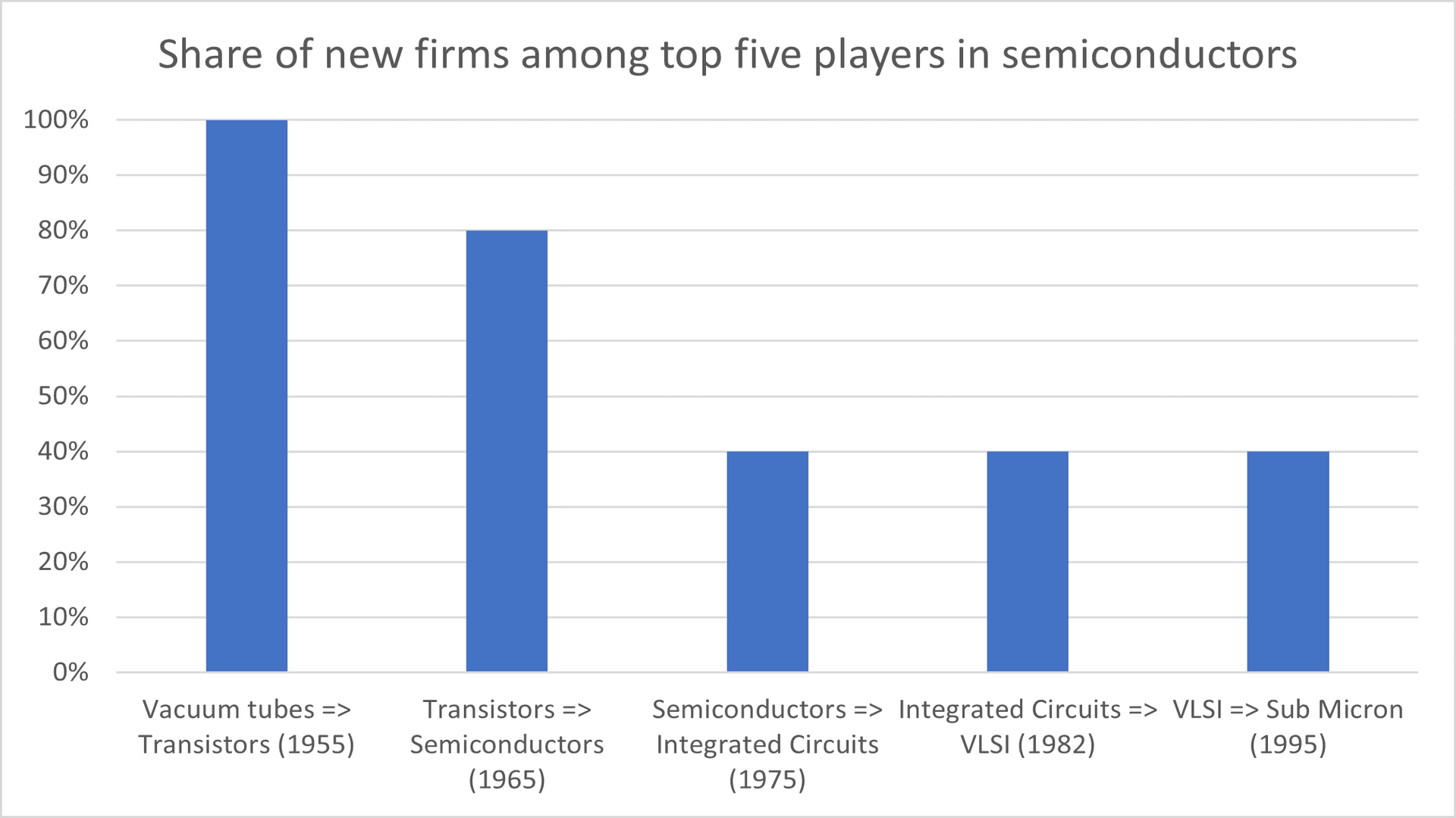

The Chip Act is particularly problematic when taking into consideration the inherent instability of the semiconductor industry. Figure X below shows the share of new firms among the top-five companies during each technological shift in the semiconductor industry. As can be seen, the successful firms are often found among the newer entrants. During each transition from one form of semiconductor technology to another, one of the leading players was replaced, often by entirely new firms. In the transition from transistors towards integrated circuits, four out of five companies were new to the industry. This pattern has been repeated in virtually every technological shift.

Dominance in the semiconductor industry doesn’t last for long. Therefore, why should we believe that the European Union’s attempts to establish the union in an industry where it has been lagging behind, should be successful?

This article is written by the guest writer Dr. Christian Sandström who is a Senior Associate Professor at Jönköping International Business School and the Ratio Institute in Sweden. Together with Karl Wennberg, he is co-editor of Questioning the Entrepreneurial State, a book which features 32 scholars who take a critical look at the revival of interventionist industrial policies. The book can be downloaded for free here: Questioning the Entrepreneurial State | SpringerLink